When it comes to entrepreneurship, selling a small business can be one of the most financially rewarding yet personally vexing stages of the journey. Owners are often surprised by how difficult a seemingly simple task can be, how long the process takes, and what merits a yes versus a no.

Part of the disconnect comes from not understanding where your business fits in the overall business-for-sale landscape. And where your business fits in this ecosystem is more often than not determined by its size.

While the Small Business Administration (SBA) considers a “small” business to be any enterprise with fewer than 499 employees, business-for-sale specialists have their own opinion on the size of a business — and why it matters when it comes time to sell.

In this article, we’ll demystify the way business brokers, merger and acquisition (M&A) advisors, and valuation specialists view the size of a small business. We’ll look at the financial metrics that have the biggest impact on selling a small business — including who will buy your business, what it’s worth, and the types of advisors who help with the business sale process.

Who this article is for: This article is geared primarily toward businesses in the lower middle market (LMM) with annual gross sales between $2M and $20M.

#1 Finding a Business Broker to Help You Sell Your Business

The process of selling a small business can often be the most difficult milestone entrepreneurs face, with the exception of surviving the startup phase. The challenges start right out of the gate with choosing the best business broker or M&A advisor to help run the sale process.

It’s tempting to think of finding a business broker as similar to finding a real estate agent. The reality is that there are millions of real estate agents and only a few thousand business brokers across the country. (Don’t be discouraged if you have to cast a wide net to even locate a good business broker in your area.)

It can also be shocking to find that, as you contact business brokers about selling your business, some may tell you that you’re not a good fit for their firm. (Have you ever met a real estate agent who turns away a homeowner wanting to sell?!)

The primary reason a business broker declines to work with a business usually has to do with its size. Intermediaries categorize the size of a business based on metrics found in financial statements, namely Profit & Loss statements, Balance Sheets, and tax returns.

When you first contact a business broker, they will typically ask you a few questions before scheduling a meeting or call. The best advisors will qualify business sellers as quickly as possible so as not to waste anyone’s time. Be prepared for them to ask about annual sales and earnings metrics from your financial statements. For example:

- Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation & Amortization (EBITDA)

- Seller’s Discretionary Earnings

- Annual Gross Income

- Adjusted EBITDA

- Net Income

If you’ve made it through an initial consultation, most business brokers will want to perform a business valuation in order to look closely at the financial performance of your business over the last three to five years. They will focus on:

- Sales growth (or decline)

- Earnings growth (or decline)

- Margins (vs. industry averages)

- Balance Sheet ratios (vs. industry averages)

Once a business broker understands the size of your business in financial terms, they will let you know if you are a good fit for them and their brokerage firm.

Using annual gross sales and EBITDA as an example, here’s how size may influence the type of intermediary who will work with you:

SIZE BY ANNUAL GROSS SALES

<$1M – Main Street Business Broker

$1M to $2M – Main Street Business Broker / LMM Business Broker

$2M to $10M – LMM Business Broker

$10M to $20M – LMM Business Broker / M&A Advisor

$20M to $200M – M&A Advisor / Investment Banker

>$200M – Investment Banker

SIZE BY EBITDA

<$500K – Main Street Business Broker

$500K to $2M – Main Street Business Broker / LMM Business Broker

$2M to $5M – LMM Business Broker

$5M to $10M – LMM Business Broker / M&A Advisor

$10M to $50M – M&A Advisor / Investment Banker

>$50M – Investment Banker

While the above categories are open to debate, the purpose of this exercise is to illustrate how the size of a small business impacts the type of M&A advisor who will work with you. Clearly, there is some overlap here. For example, if you own a business that does $11M in annual sales with $1.9M in EBITDA, you may find either an LMM business broker or an M&A advisor who is a good fit for you and your business.

Or not. There are other reasons besides size why an intermediary may say you’re not a good fit. These can include the business carrying too much risk, or the financial records not being sufficient to withstand the due diligence process.

[Note: If you’re unable to find a business broker to work with, read our guide on how to sell your business without a business broker. There are also online marketplaces like BizBuySell that offer DIY resources for business sellers.]

#2 Putting a Price on Your Business

Common sense would say that a successful business that does $8M in annual gross revenue is going to sell for more than a business that does $6M. But business valuation is rarely that straightforward.

It’s also easy to assume that the value of your business equals the business assets minus its liabilities. However, the value of your company — which informs how brokers set an asking price — is largely determined by the size of two financial metrics: pre-tax earnings and the valuation multiple.

Common pre-tax earnings metrics used in business valuation include EBITDA, adjusted EBITDA, EBIT, and Seller’s Discretionary Earnings (SDE). As a business owner, you have quite a bit of influence over this number.

When it comes to small business valuation multiples, some things are in your control while others are not.

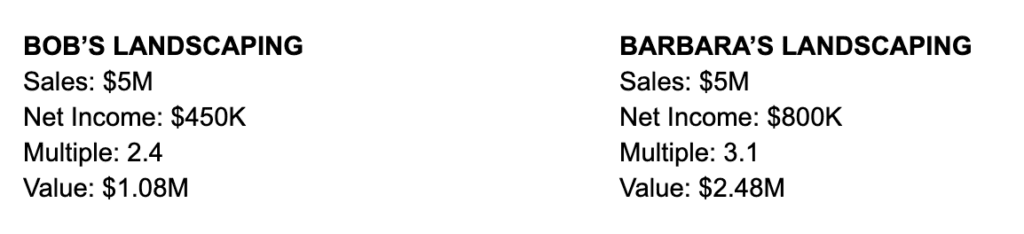

Let’s look at a quick example of two similar businesses. Both are healthy companies with $5M in annual sales. Are they both worth the same in a sale scenario? In order to answer that question, we’ll need to determine pre-tax earnings and a valuation multiple.

After a thorough business valuation, we find that Bob’s Landscaping has mostly residential customers, while Barbara’s works exclusively with commercial accounts. Having a more desirable customer base means Barbara’s is more profitable (16% net margin versus Bob’s 9%).

Furthermore, we find that Barbara’s business has a higher valuation multiple assigned to it for a number of reasons. These include having customer contracts in place with a 98% annual renewal rate and being the market leader in both sustainable design and landscape lighting.

This quick example illustrates how profitability and other factors influence the multiple, which in turn dictates the value — and sale price — of a business. At first glance, annual sales don’t say much about what a business is worth.

[Note: Valuation methods can and do vary by type of business. There are some industries that value a business based on annual sales, like insurance, accounting, financial services, and some franchises.]

In general, the bigger the business the lower the risk, therefore the higher the multiple. However, beware of quick, superficial pronouncements about the value of any business: There’s a lot of art and science required to arrive at a reliable number.

#3 Who Are the Potential Buyers for Your Business?

Business buyers can be lumped into two broad categories: strategic and financial. The size of your business will have a big impact on the type of prospective buyers it can attract.

Selling a Small Business to a Strategic Buyer

Strategic buyers are often considered the ultimate interested buyers, as they may be willing to pay a premium in order to acquire a business. Strategic buyers come in all shapes and sizes, but they are all interested in one thing: growth through acquisition.

A strategic buyer may want to expand into new territory, sell a new product line to existing customers, sell existing products to a new customer demographic, acquire employees or intellectual property … you name it.

Along with having their own reasons, they also have their own, internal process for determining how much they are willing to pay for a business. Unless they are a public company, it can be difficult to ascertain how they make decisions about the companies they buy.

In general, smaller businesses rarely generate interest from strategic buyers. Even if it might make sense for them, it’s not worth expending their resources in terms of both time and money to acquire a company that is too small.

What is “too small” for a strategic buyer? That depends entirely on them. However, it’s safe to say that strategic buyers are almost never interested in Main Street businesses. Although smaller strategics are often interested in acquiring businesses in the lower middle market.

[Note: Most strategic buyers have a strict set of investment criteria they follow. I once connected with someone in Corporate Development at Samsonite USA using LinkedIn. He told me that, while he liked the company my firm was representing, they only looked at businesses with at least $200M in annual sales.]

Selling a Small Business to a Financial Buyer

It’s much more likely to see financial buyers active in the purchase of Main Street and lower middle market businesses. Financial buyers include:

- Individuals

- Partnerships

- Private Equity Groups

Unlike strategic buyers, financial buyers have no strategic “rationale” for acquiring a business: They are interested in acquiring a stream of earnings. Yes, they are considering many other characteristics of a business, but they are focused largely on cash flow from operations and are careful not to overpay for a business.

If the new owner is a financial buyer, like a private equity group, they likely plan to grow your business and then have their own sale — often to a larger financial or strategic buyer — after an appropriate period of time.

In summing up qualified buyers, it’s difficult for most small businesses to generate interest from strategic buyers. It’s best to prepare your business for sale with a financial buyer in mind. It will increase the odds of a successful sale and does nothing to prevent a sale to a strategic buyer if you do get lucky.

#4 Realistic and Available Exit Strategy Options

There are a number of ways to exit a business. The primary exit strategies for business owners include:

- Merger

- Acquisition

- Family Succession

- Management Buy-In

- Management Buy-Out

- Initial Public Offering (IPO)

- Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP)

Several of these options simply aren’t feasible for lower middle market businesses. For example, a recent study showed that the median value of U.S. businesses that had an IPO in 2021 was $177M — hardly a “small” business.

It can also be difficult for small business owners to exit through an ESOP. In fact, ESOPs can only be installed after going through a rigorous feasibility study. While they have some very attractive tax advantages — and can be a good way to reward employees and increase retention — they are expensive to install and maintain. ESOPs work best for companies with a large number of employees, and a transparent corporate culture.

Family succession plans and management buyouts work well when the owner is more concerned with legacy than the selling price. Selling to an internal buyer — like family members or managers — also comes with a lower valuation and a longer payback period.

The majority of small business owners have the bulk of their net worth trapped in the value of their biggest asset: their business. For this reason, sale proceeds typically play a significant role in retirement planning and maintaining a post-sale lifestyle.

Most small business owners only have a few realistic exit strategy options: Sell to an internal or external buyer or wind down and liquidate. For the smallest businesses, the latter may be their only option.

Make Sure You’re Building a Sellable Business

Many business owners reach the end of their entrepreneurial journey only to find that they’ve built a business with no transferable value. This doesn’t have to be the case. If you want to cash in on years of hard work, play the odds and build your business so that it will attract an outside financial buyer and can be sold at market value.

Get ahead of the game by enlisting the help of a seasoned business broker well in advance of selling a small business. They can give you insight into how your business fits into the business-for-sale ecosystem, and how to make your business more attractive to buyers when you’re ready to sell.

Reach out to the advisors at Allan Taylor & Co. to learn more about selling your business, having your business valued, or preparing for a future sale. We’re here to help!

Barbara Taylor is the co-founder of Allan Taylor & Co. You can follow her on LinkedIn and Twitter.