When it comes to misconceptions surrounding the sale of a business, small business valuation multiples may be the most routinely misunderstood – with the most profound consequences. How can one simple number cause so much confusion? What does the multiple say about a business? And is “ten times” considered the norm, pie in the sky, or below market?

The concept of a valuation multiple is fairly easy to understand, but it is completely meaningless without the proper context. And there is a lot of context that goes into determining an appropriate multiple when valuing a small business.

In this article, we’ll start by looking at real-world multiples from completed transactions in the lower middle market. We’ll also discuss what small business valuation multiples represent, why they matter, and why other factors may matter more when selling your business.

How Multiples Are Used to Value a Small Business

A common valuation method for privately-held businesses is using a multiple of earnings. The earnings metric is usually a pre-tax measurement, like one of the following:

- Seller’s Discretionary Earnings (SDE)

- Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization (EBITDA)

- Adjusted (or normalized) EBITDA

- EBIT

- Discounted Cash Flow (DCF)

You may notice that Revenue is not on this list. Multiples of revenue are much less common, and tend to be used only in specific industries. Even in cases where a multiple or percentage of revenue is considered acceptable, earnings will still be heavily scrutinized by a buyer.

Whether to use a multiple of EBITDA, EBIT, or another pre-tax earnings metric to find the value of a business depends on the industry and certain characteristics specific to that business. For instance, EBIT may be considered more appropriate for capital-intensive businesses while adjusted EBITDA is commonly used for asset-light businesses with strong cash flow and intangible assets.

Regardless, using a simple example where EBITDA is $1M and the multiple is 4.0, the value of the business would be $4M. So, where did the 4.0 come from?

Finding Valuation Multiples for Your Business

Assuming you know what pre-tax earnings are for your business, all you need to do is find one other number: An accurate multiplier. Sounds like a quick way to determine what your business is worth, but finding a realistic multiple is easier said than done.

There is no readily available, public multiple listing service (MLS) for sold businesses in the way that there is for real estate. Small businesses are bought and sold every day without anyone knowing the details, or even that a change of ownership has taken place.

Business brokers and merger and acquisition (M&A) professionals do, however, have access to various databases that offer guidelines based on completed transactions across the country. Where does the information come from? It’s customary for M&A industry professionals to contribute aggregate data about a transaction to these sources after a deal has closed, (identifying details of the business are kept confidential).

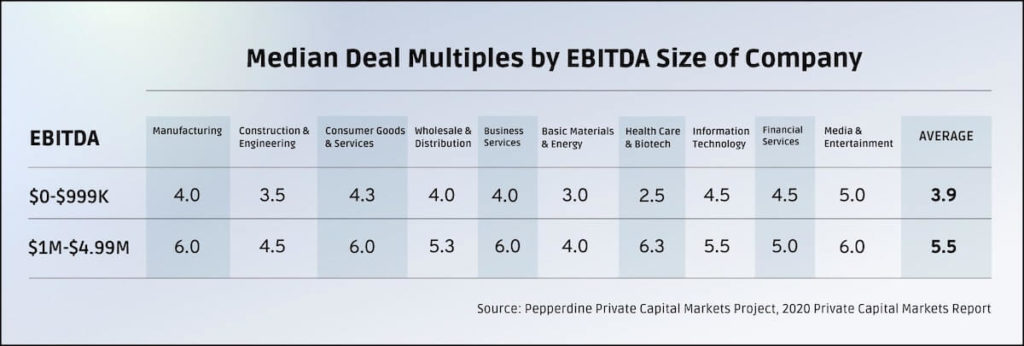

One such resource is the Pepperdine Capital Markets Project. Here is some information on real-world EBITDA multiples pulled from their 2020 Private Capital Markets Report:

Again, the information above was submitted by M&A professionals – including investment bankers, lenders, private equity investors, and business brokers – based on transactions completed by their firms in 2020. Using multiples from public company transactions is considered useless when valuing businesses in the lower middle market. That’s why resources like the Pepperdine report are so important.

There are a couple of things to keep in mind when looking at the data.

First, when someone says a business sold for “five times” the first thing to ask is “five times what?” In the data above, we’re looking at a multiple of unadjusted EBITDA. The multiple changes when you use a different earnings metric. There’s a big difference between using a multiple of EBITDA versus a multiple of SDE. It’s important to make the distinction so you’re making an apples to apples comparison.

Second, you can see that small business valuation multiples vary by both the industry and the size of the business being valued. A health care company with less than $1M in EBITDA sells for a much lower multiple than one with $4M. This illustrates a general rule about valuation multiples: The bigger the business the higher the multiple. Another general rule that becomes evident here is that some industries fetch higher multiples than others. (More on both of these general rules below.)

One more thing we can quickly see from this real-world data is that lower middle market businesses don’t seem to be selling for a multiple of ten times EBITDA. In fact, a ten multiple would be double the average we see here. Double!

What Does a Valuation Multiple Say About a Business?

It’s worth nothing that valuation multiples are often expressed as a range. For instance, a business valuation may conclude that the expected multiple range for a business is between 3.0 and 4.3 based on similar businesses that have sold in that industry. Using a multiple range allows an analyst to apply their professional judgement about where on the range that business may fall.

In this sense, the multiple can be thought of like a grading scale or report card of sorts for your business. Whether your business scores at the lower or higher end of the multiple range clearly makes a big difference in its value. Two things have the biggest impact on where a business falls on a multiple range.

Level of Risk in the Business and/or Industry

One of the functions of a multiple is to capture the amount of risk involved in owning a particular business. Owners often become numb to the inherent risks in their business. Buyers, on the other hand, do everything they can to uncover all of the risks associated with their investment. Generally speaking, the lower the multiple the higher the risk.

Another way to look at how the multiple corresponds to risk is to use the reciprocal to express a rate of return. A 3.0 multiple translates to a 33.3% rate of return. The more risk undertaken, the higher the reward required to make that risky investment worthwhile.

There are a number of reasons why smaller businesses carry outsized risk for potential buyers. Many smaller businesses have risk baked into them in the following ways:

- Reliant on one or a few people (i.e., owner and/or family members)

- Vulnerable to operational or economic downturns

- Weak competitive position

- Lack of proper financial controls

- Incomplete organizational structure

- No long-term, strategic planning

Risk factors like these (and others) will pull a business down to the lower end of the multiple range. In some cases, the amount or risk can render the business unsellable.

Opportunities for Future Growth

In addition to having less risk, businesses that have clear opportunities for future growth can command a multiple at the higher end of the range. Attractive growth opportunities can include:

- Ability to scale quickly under new ownership

- Desirable geographic location

- Demographic trends

- Expanding industry or sector

An example of the latter would be the green energy industry, where multiples have been high for years thanks to the continued, long-term shift away from fossil fuels. Of course, the opposite is true: Few prospective buyers are looking for a business in a declining industry.

Going back to the report card analogy, demonstrating a trend of strong year-over-year growth (accompanied by reliable financial statements) will bump the multiple to the higher end of the range while declining or inconsistent financial performance usually does the opposite.

Do Business Owners Have Any Control Over the Multiple?

If we look at the two-part valuation equation above – earnings times multiple – the business owner has all kinds of control over earnings from business operations. But is there anything you can do to influence the multiple?

The short answer is not much. As you can see from the data we pulled, buyers in your industry end up determining a realistic multiple range for your business. However, there are still things you can do to boost the valuation multiple when preparing your business for a sale. These include:

- De-risking the business as much as possible

- Developing a strong upper management team

- Growing the business by increasing both revenue and earnings

- Dominating a niche and/or have a clear competitive advantage

- Creating a plan for additional growth that can transfer to a new owner

Beware the Newsworthy Valuation

Sky-high multiples are the stuff of legends in the M&A world. Everyone wants to brag about them, whether it’s the seller who gets a massive payday, or the broker who seals the deal. But if you own a small business, it’s best to take these stories with a grain of salt.

First, big deals that make the news have almost nothing in common with the millions of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) that account for 90% of GDP and 50% of employment worldwide. In fact, what is true in the small-business-for-sale marketplace is often the polar opposite of the big business reality.

Second, stratospheric valuations for any size business or industry are the exception not the rule. There’s a reason they’re called unicorns: They are rare to the point of being almost mythical. Many of these valuations end up in a tailspin shortly after they’re announced anyway (e.g., WeWork, Theranos, cryptocurrencies, etc.).

Some of these deals, however, made perfectly good business sense for the buyer.

Can We Learn Anything From Facebook and Instagram?

One of the biggest headlines of 2012 was Facebook’s acquisition of Instagram. Facebook valued Instagram at $1B when it was only two years old, had 13 employees and no revenue. The valuation was considered shocking at the time. But was $1B a crazy number?

Believe it or not, there are a few useful take-aways for small business owners from the Facebook/Instagram deal.

Always Know the Market Value of Your Business

Instagram was valued at $500M just prior to Facebook’s acquisition. When a company is backed by venture capital it’s forced to do things that are prudent, like always knowing the value of what you own. This goes a long way towards managing a company in a way that increases its value. It also lets you know unequivocally if someone just offered you twice (or half) what your business is worth.

TIP: If you’ve never had a professional business valuation, get one for your business immediately. Even if you don’t have plans to sell in the short-term, a valuation will help you make decisions in the meantime that increase – and don’t decrease – value. Plan to have the valuation updated every one to two years. (Many owners get or update a valuation after they’ve closed the books on a fiscal year, or as soon as their taxes are done.)

Only a Strategic Buyer Knows What Your Business Is Worth to Them

While the Instagram valuation seemed outrageous to everyone at the time, the buyer clearly felt otherwise. Facebook determined that making Instagram an offer they couldn’t refuse was still cheaper and faster than building their own photo-sharing app from scratch. In other words, there was a strategy that supported their valuation. For Facebook, $1B wasn’t a crazy number. The valuation made sense to them and ended up looking like a bargain within five years of closing.

Deal Structure Ultimately Determines Value

One last caveat about these stories is that we don’t really know what the final purchase price was, especially when you’re talking about privately held versus publicly traded companies. Deal structure has as much – some say more – to do with the price paid for a business as the multiple. What did a purchase price of “five times” include? Was there a significant amount of working capital included in the price? Was there a performance based earnout involved? If so, what was it worth, and was it fully satisfied?

The upshot is that you would need to know all the details about a transaction in order to know what the seller received from the sale. ”Five times” might have been the buyer’s initial offer based on the seller’s asking price, not the final purchase price. Only those close to the deal know exactly what the seller received.

Unrealistic Expectations. Unrealized Dreams.

If you’re pondering the story of Facebook buying Instagram and thinking “my business is no Instagram” you’re right. Getting stuck on an unrealistic value for your business – including an inappropriate multiple – results in missed opportunities to sell to a good buyer at a fair price when the time is right. And while it may not make headlines, that is still an impressive milestone that most entrepreneurs never achieve.

The advisors at Allan Taylor & Company are ready to help you understand the value of your business. Let’s start the conversation today.

Barbara Taylor is the co-founder of Allan Taylor & Co. You can connect with her on LinkedIn.